Murièle Modély

le poème et toi vous êtes beaucoup de noir sur un peu de blanc

in Tu écris des poèmes

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

le poème et toi vous êtes beaucoup de noir sur un peu de blanc

in Tu écris des poèmes

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/6d/72/6d7209ae-1945-4682-b1c1-29a1a22711c4/misliyacave2-wr2.jpg)

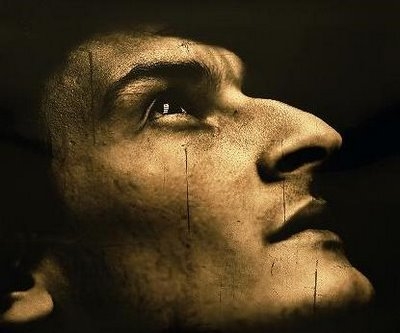

For decades, scientists have speculated about when exactly the bipedal apes known as Homo sapiens left Africa and moved out to conquer the world. That moment, after all, was a crucial step on the way to today’s human-dominated world. For many years, the consensus view among archaeologists placed the exodus at 60,000 years ago—some 150,000 years after the hominins first appeared.

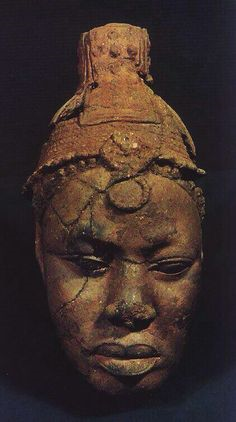

But now, researchers in Israel have found a remarkably preserved jawbone they believe belongs to a Homo sapiens that was much, much older. The find, which they’ve dated to somewhere between 177,000 and 194,000 years, provides the most convincing proof yet that the old view of human migration needs some serious re-examination.

The new research, published today in Science, builds on earlier evidence from other caves in the region that housed the bones of humans from 90,000 to 120,000 years ago. But this new discovery goes one step further: if verified, it would require reevaluating the whole history of human evolution—and possibly pushing it back by several hundred thousand years.

The find hinges on the partial jawbone and teeth of what appears to be an ancient human. A team of archaeologists unearthed the maxilla in Misliya Cave, part of a long complex of prehistoric settlements in the Mount Carmel coastal mountain range in Israel, along with burnt flints and other tools. Using multiple dating techniques to analyze the crust on the bones, the enamel of the teeth and the flint tools found nearby, researchers honed in on the astounding age.

“When we started the project we were presumptuous enough to name it ‘Searching for the origins of modern Homo sapiens,’” says Mina Weinstein-Evron, an archaeologist at the University of Haifa and one of the authors of the paper. “Now we see how right we were to give it such a promising title ... If we have modern humans here 200,000 years ago, it means evolution started much earlier, and we have to think about what happened to these people, how they interacted or mated with other species in the area.”

The Misliya jawbone is only the most recent piece in what has become the increasingly complex puzzle of human evolution. In 2016, scientists analyzing ancient Neanderthal DNA in comparison with that of modern humans argued that our species diverged from other hominin species more than 500,000 years ago, meaning Homo sapiens must have evolved earlier than believed.

Then, in 2017, researchers found human remains in Jebel Irhoud, Morocco that dated to 315,000 years ago. Those skulls showed a mixture of modern and archaic traits (unlike the Misliya bone, which has more uniformly modern traits). The researchers declared that the bones belonged to Homo sapiens, making them the oldest bones from our species ever found, once again pushing back the date at which Homo sapiens appeared.

Yet neither of these two studies could offer definitive insight into when, precisely, Homo sapiens began moving out of Africa. That’s what makes the Misliya jawbone so valuable: if it is accepted as a Homo sapiens fossil, it offers concrete proof that we humans moved out of Africa much earlier than previously believed.

“It’s just jaw-dropping, no pun intended, in terms of its implications,” says Michael Petraglia, an anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History who wasn’t involved in the recent study. “This find is telling us that there were probably early and later movements out of Africa. We may have gotten out of Africa and into new environments, but some populations and lineages may have gone extinct repeatedly through time.”

In other words, the individual from Misliya isn’t necessarily a direct ancestor to modern humans. Maybe it belonged to a population that went extinct, or one that exchanged genes with some Neanderthals and other hominins in the area.

The bone is another thread in a vastly complicated tapestry telling the story of hominin evolution over the past 2 million years. During the Pleistocene, scores of hominin species romped around the globe; Homo sapiens were only one of many bipedal apes. Neanderthal remains from 430,000 years ago have been found in Spain, while 1.7 million-year-old Homo erectus fossils were unearthed in China. How did all these groups interact with one another, and why are we Homo sapiens are the only ones remaining? These are all mysteries yet to be solved.

But in the case of the Misliya individual, the connection to Homo sapiens in Africa is even clearer than normal, thanks to the huge collection of tools buried in Misliya Cave. They’re classified as “Mousterian,” a term for a specific form used during the Paleolithic. “They’ve got a direct association between a fossil and a technology, and that’s very rare,” Petraglia says. “I’ve made arguments that dispersals out of Africa can be tracked based on similar technologies during the Middle Stone Age, but we haven’t had fossils to prove that in most places.”

While the discovery is thrilling, some anthropologists question the usefulness of focusing so intensely on the moment humans left Africa. “It’s pretty cool,” Melanie Chang, professor of anthropology at Portland State University, says of the new discovery. “But what its significance is for our own ancestry I don’t know.”

Chang, who wasn’t involved in the new study, asks if we can’t learn more about human evolution from Homo sapiens dispersals within Africa. “If the earliest modern humans are 350,000 years and older, we have hundreds of thousands of years of evolution happening within Africa. Is leaving Africa so special in itself?” she says.

Petraglia’s main critique is that Misliya Cave is in close proximity with other important finds, including hominin bones from Qafzeh, Skhul, Tibun and Manot Cave, all in Israel. The area is a treasure trove of human prehistory, but the intense spotlight on a relatively small region is likely biasing the models for how humans moved out of Africa, he says.

“There are very large areas of West Asia and Eurasia in general that have not even been subject to survey, never mind excavations. The way it’s portrayed [in this research] is the out of Africa movement went straight up into the Levant, and that happened many times,” Petraglia says. “But if you look at a map of the connection between Africa and the rest of Eurasia, we can expect these kinds of processes to be happening over a much wider geographic area.”

Even with those caveats, the new find remains an important element to add to our understanding of the past.

“If human evolution is a big puzzle with 10,000 pieces, imagine you only have 100 pieces out of the picture,” says Israel Hershkovitz, a professor of anatomy and anthropology at Tel Aviv University and one of the authors of the new study. “You can play with those 100 pieces any way you want, but it will never give you the accurate picture. Every year we manage to collect another piece of the puzzle, but we are still so far from having the pieces we need for a solid idea of how our species evolved.”

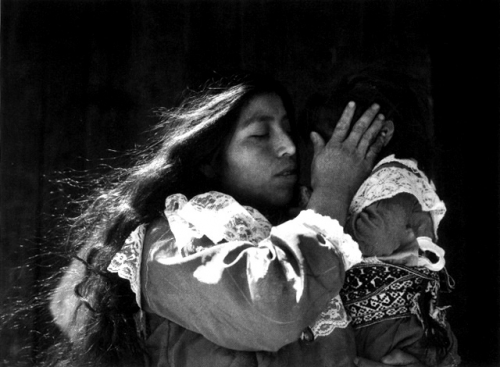

Mujeres mazahuas. San Agustín Metepec, Estado de México